I learned about the different wines produced in the Almaty region on a recent trip to Kazakhstan. While I knew Kazakh wine culture and production ran deep, I didn’t know much about production today, the local market for wine, and the state of the wine industry in Central Asia. It was an educational and tasting journey I was happy to embark upon.

A Brief History of Kazakh Wine

The growing of grapes and the production of wine in Kazakhstan dates back centuries. Vineyards were a common sight in the former Soviet Union, particularly in the south of Russia and in parts of Georgia and Ukraine. These vineyards stretched into parts of Kazakhstan, particularly in the southeast of the country.

By the early 1980s, there were vineyard plantings of around 28,000 hectares (a little over 69,000 acres) in Kazakhstan. However, shortly thereafter in 1985, there was a complete ban on alcohol by USSR leader Mikhail Gorbachev. Known as the Anti-Alcohol Campaign, it wreaked havoc on the wine industry in Kazakhstan. As a result, many farmers pulled out their vines to plant other crops such as grains and fruit trees. This was a huge blow for Kazakh wine as the vineyard plantings dwindled and the industry took a massive hit.

Not all was lost, however, although the road was bumpy. Kazakhstan declared its independence from the Soviet Union towards the end of 1991. After a struggle with its new economic system, many farmers and other players in the agricultural sector were forced to shut down production. Vineyards lay dormant, and it was not until years later that scientists decided to get involved.

Extensive tests were conducted, and more than 500 grape varieties were planted in Kazakh vineyard nurseries. This was crucial as little was known about which grape varieties would thrive and which would fail. The native Georgian varieties of Saperavi and Rkatsiteli prevailed thanks to their resilience to harsh Kazakh weather and their high-yielding abilities.

Native Kazakhstan Wine Grape Varietals

The two notable native Kazakh grape varieties are Saperavi and Rkatsiteli, a red and white grape respectively. Both Saperavi and Rkatsiteli originated from Georgia, a stone’s throw from Kazakhstan. After extensive research and testing of soil and climate, it was felt that these two varieties would thrive best given the climate in the country.

Saperavi is a medium to full-bodied red grape varietal that is dry on the finish with a deep purple hue to it. You can expect high alcohol, high tannin, and high acidity from Saperavi, with characters of plum and blackberry, licorice, earthiness, and tobacco.

Rkatsiteli, on the other hand, is a light-bodied, dry white varietal with medium alcohol, little to no tannin, and high acidity. You can expect herbaceous characters such as tarragon and fennel coupled with tropical fruit notes such as lime and pineapple.

Kazakhstan experiences large summer and winter temperature differentials, with summer temperatures hitting 95+ F, and winter temperatures plummeting below 40 F. There is also a natural temperature controller thanks to the altitude. Sitting at around 3,200 feet above sea level, there are cool breezes during the summertime that regulate temperatures and cause night temperatures to drop significantly. This is highly favorable as it helps the grapes retain their natural acidity and removes the need for acidification of the wines.

Aside from these two native Kazakhstan wine grape varieties, there are a number of French varieties that are grown in new vineyards in the country, too. You can expect to find Pinot Noir, Riesling, Cabernet Franc, Gewurztraminer, Chardonnay, Malbec, and Shiraz.

Commercial Production of Wine in Kazakhstan

The Assa Valley, found in the southeastern part of Kazakhstan, is one of the most notable regions for grape growing and wine production in the country.

It was here that Zeinulla Kakimzhanov discovered the “sleeping vineyard” – vines found in one of the abandoned Soviet vineyard from 20 years earlier. The vines had been growing wild and were untouched for all this time. As a result, they were incredibly resilient, had a deep root system that was immune to phylloxera, and were ungrafted.

After seeing this amazing potential in the vineyards, Kakimzhanov was advised to pull out the vines to plant new French varieties in the area. Kakimzhanov, who was extremely passionate about wine, was deeply interested in the resilience of the old Soviet vineyard. As a result, he left the vines so live another day, giving them a second chance.

This was the start of the commercial production of wine in Kazakhstan and the Arba wine company. Thanks to the visionary ideas of Kakimzhanov, that old Soviet vineyard remains today.

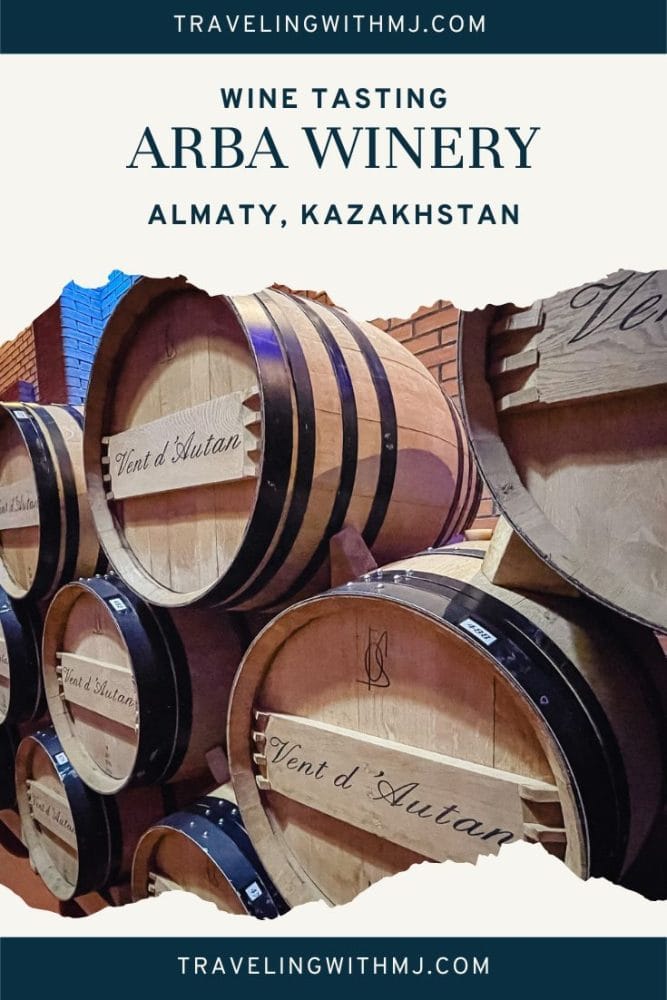

Since 2010, Arba winery has been producing wines from these vineyards. It took a few years to get them up to speed – some serious gardening was required in order to restore the vineyards to their former glory including felling trees, digging of irrigation trenches, trellising, and pruning.

The Arba Winery makes use of pockets of vines that date back more than 40 years and with this, sees an overall increase in quality. With older vines, the yields tend to be smaller but there is a definite increase in overall intensity and quality in the wines.

But new varieties of grape were also planted, and the expansion of the commercial Kazakhstan wine scene was in full swing. With the introduction of French varieties such as Gewurztraminer, Cabernet Franc, Chardonnay, and Riesling as well as the construction of a brand new, state-of-the-art winery, Arba showed the world that they were open for business.

Wine Tasting at Arba Winery

I visited Arba Winery as part of a tour option on my recent trip to Kazakhstan. I was interested in learning more about Kazakhstan wine; I was unable to locate any at home. We had an enjoyable afternoon at the winery that included a tour and explanation of the wine process (with an interpreter), tasting of several of the winery’s current selections, followed by lunch in the vineyards.

Official website here.

Like most wine tasting that I do, I liked some of the wines and didn’t like others. Since I likely won’t be able to find Kazakh wine here at home, although it is available in other parts of the United States, I purchased two bottles to bring home with me – Lagyl Arba Saperavi Reserve 2013 and Kyzyl Bastau 2018.

Lagyl Arba Saperavi Reserve 2013

Tasting notes: Deep, dark red-violet in color. Berries, with a hint of minerality, on first taste. This wine won a bronze medal in the Saperavi World Prize 2017 Awards.

My thoughts: This was unusual and lovely, full of rich berry flavors from the first taste. A touch of herbal notes on the finish. The flavor was as rich and chewy and the color was dark and inky. All around, a good red wine for my personal palate. I bought a bottle to bring home and share with Tony. I think it will open up with decanting, and we’ll probably drink it fairly soon. Again, this isn’t available locally. Estimated price, if you can find it, is $31 (plus shipping).

Kyzyl Bastau 2018

Tasting Notes: A Merlot, Pinot Noir, and Saperavi blend. Lovely fleshy blackcurrant and cedar, with spice and leather. Long flavors on the finish. This wine won a bronze medal at the International Wine Challenge.

My thoughts: This wine was often found on menus around Almaty, and this particular year (along with 2019) are the best to showcase the blend. I noticed flavors of spice and leather, but didn’t notice a particularly long finish. It may benefit from decanting. I bought a bottle to take home because I’d love to see how this continues to open up and evolve. While it’s not going to rival any of the Washington or California red blends, it was tasty and interesting and I’m looking forward to sharing it with some friends who are wine lovers. This isn’t available anywhere nearby, a major reason for bringing it home, but estimated price based is about $9 (plus shipping).

Final Thoughts

While the wine in Kazakhstan is still evolving as the industry expands and the demand and interest grows, it is still very much unknown. Wineries like Arba are at the forefront of the industry and pioneers like Zeinulla Kakimzhanov are a driving force behind the Kazakhstan wine movement.

There is an underlying struggle with wine quality and consistency at present. I have no doubt, however, that Kazakh wine will evolve into a force to be reckoned with in the coming years. They have a well-suited climate with old vineyards and modern wine-making facilities. All the ingredients are there to be able to make great wines. Its just a matter of time before these wines will make their way to the rest of the world.

Disclosure

I visited Kazakhstan as part of an organized group trip for the Digital Publishers Council of SATW (Society of American Travel Writers). Our group trip was sponsored by Kazakhstan Tourism, USAID, and their partners. The tasting and inner at Arba Winery was part of our organized activities. All sponsors understand and respect the integrity of independent storytelling and reporting and have not exerted influence about coverage. The content of this post reflect my experiences and opinions, and are not necessarily the views of Kazakhstan Tourism, USAID, or the US Government.

Save to your favorite Pinterest boards